30 January 2019

The Garrison Town of Québec

A look back at the city’s military history

Québec is a city with a wealth of history—memories are blended into its built heritage to call forth important aspects of the past. Part of this military heritage is the fact that until 1871 Québec was home to a British garrison. The regiments stationed here, tasked with defending the country, also played a significant role in Québec’s cultural and social life. Read on to learn more about that aspect of Québec’s military past.

Soldiers in New France

No sooner had Québec City been founded by Samuel de Champlain in 1608 than it became the linchpin of the colony’s system of defence. The site was ideally suited not just to anchor the French presence in North America, but also to beat back any attempt by the people in the area, First Nations, to rid themselves of that presence. And so, the governor built Fort Saint Louis on the promontory of Cape Diamond and assigned a garrison of a few dozen soldiers to it.

The garrison became increasingly important as years passed and New France’s defensive system expanded. The colonial government began preparations for renewed war against the Iroquois Confederacy in the 1680s and requested new troops. The response arrived in 1683 in the form of three companies with a total strength of 150—the Compagnies franches de la Marine—under the direct authority of the king. By the 1750s there would be forty such companies in New France, a number of which were stationed in Québec City.

The garrison settles in

Much of the town was destroyed by bombardment during the Seven Years War and needed to be rebuilt. With the 1763 Treaty of Paris, New France and its capital fell under British rule, but the new owners were far from secure and set to work fortifying their possession, adding a permanent garrison to put a damper on any French ideas of a triumphal return.

Québec was thus transformed into a real garrison town, with barracks, a redoubt, powder magazines, and a citadel. Its defensive importance was further consolidated in 1775 and 1776 during the American Revolution, from which Québec emerged as the capital of the British Empire in North America. At that time one out every four people in Québec was a British soldier, and in some years the strength of the garrison reached 1700. A military population that size needed its own services, and one such institution was the Garrison Hospital, also known as the Saint Louis Hospital after the street it was built on. In a disaster or epidemic, the hospital could accommodate hundreds of patients.

No wonder the military presence marked the city so deeply, both physically and socially.

Enlivening Québec’s cultural life

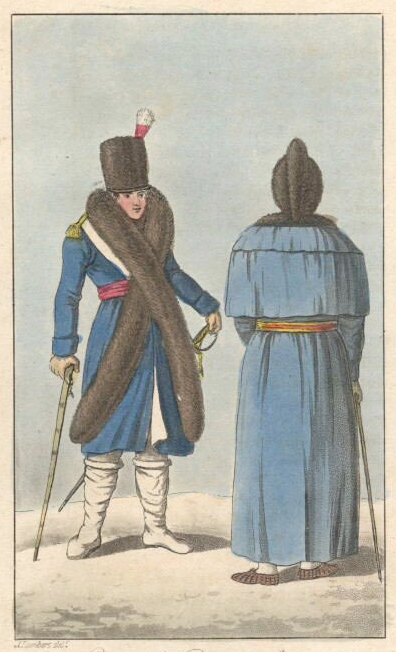

In the late 18th century, garrison officers and soldiers figured prominently in the Québec’s theatre, music, and general cultural scene. They took part in civic holidays and celebrations and joined the local upper crust for banquets, charity balls, and much more. The garrison was a tangible symbol of the power of the British Crown and as such was expected to see and be seen.

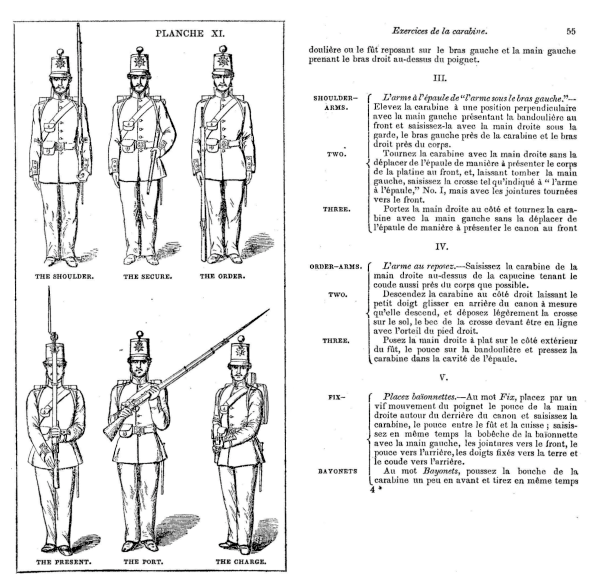

Many were the displays of pomp and circumstance, to the delight of the general public. The regiments often did drill on the Esplanade and the Plains of Abraham, staging live-fire exercises and even mock battles. Their agility, dexterity, discipline, and adherence to protocol were much admired. The regiments marched regularly on the parade square of Château Saint Louis (Place d’Armes) and on summer evenings the band would play for an hour or two when the weather was fine. It wasn’t long before the concerts became a weekly event, continuing until 1837.

Some of the officers hosted private chamber music soirées or recitals with small choirs and soloists. Others even organized subscription concerts, with the proceeds going to local charities.

The garrison was a driving force in Québec theatre in the 19th century. Officers went into acting and appeared in small local theatre companies. In 1815, plays were being produced at the Union Hotel, at Place d’Armes, and in Mailhot’s hotel on John Street (rue Saint-Jean). The Royal Circus on Saint Stanislas, which became the Royal Theatre in 1834, was another venue where theatre buffs civilian and military, English- and French-speaking, met and mingled.

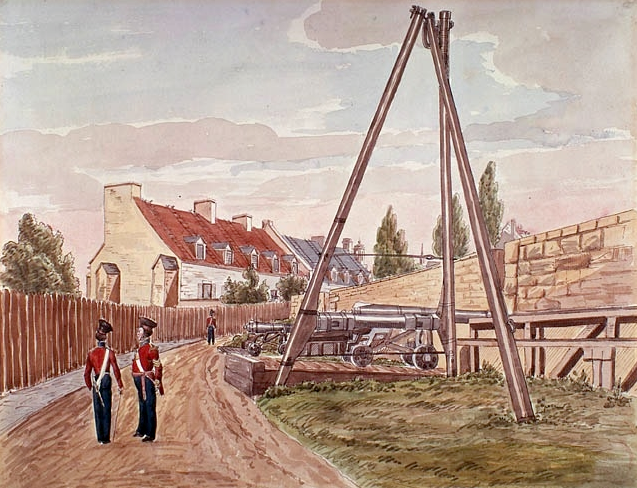

Artillery Barracks and Gun Placement, Quebec, circa 1830, James Pattison Cockburn. Library and Archives Canada, 1989-262015

One of the officers who saw duty at Québec was artist-officer James Pattison Cockburn. In 1826 he was given command of the Royal Regiment of Artillery and came to Québec until his tour ended in 1832. In his six years here Cockburn produced an impressive number of sketches and watercolours set in the landscapes of Upper and Lower Canada, particularly in the area around Québec. Even today his pictures of local streets remain a rich source of insight into daily life at the time, both social and spiritual.

Saying goodbye to the garrison

The garrison shrank in proportion to the city between 1830 and 1860, as immigrants from Ireland and other countries flooded in. The officers and soldiers living in the artillery barracks and the citadel mingled with the locals, patronized the shops, and hung out at local taverns, but rarely married French Canadians. Few in fact were here for more than three years. When Confederation rolled around in 1867 the garrison’s total strength was 945—about one soldier for every 40 civilians, or about 2.5% of the population.

By then the sabre rattling along the U.S. border seemed a distant echo. For the British authorities, security ceased to be an issue. A permanent British military presence no longer being required, the decision was made to withdraw the garrison. And so it was that on November 11, 1871, all members of the 60th Regiment, the Royal Artillery, and the Royal Engineers marched out from the Citadel and Artillery Park in full dress to parade for the last time, through the streets of the Upper Town down to the Lower Town, singing “Auld Lang Syne” and “Goodbye Sweetheart, Goodbye.” Before a crowd of wellwishers, they boarded HMS Orentes and sailed off into the city’s military history. A new chapter had begun…

Other units would step in to relieve them, such as the Royal 22e Régiment based in the Citadel, and of course the Voltigeurs at the Voltigeurs de Québec Armoury.

To this day there are signs of the former British garrison everywhere you look. If you’re interested in military heritage, you’ve come to the right place!